A Fascinating Chapter in Lynchburg’s Early Medical History

Dr. Terrell began his life in Lynchburg. His family were Quakers who became Methodist in the interest of keeping their slaves; a practice which was not allowed in the Quaker religion. His father, Christopher Terrell, was a doctor, and moved the family to Missouri, and then Pennsylvania for a time. In his early teen years, John Jay was sent to live with his devout Quaker aunt in Lynchburg where his Quaker faith was reignited, and he practiced the faith for the rest of his life. Education had always been a core value of the Terrell family, and John Terrell earned his first degree at Emory and Henry. However, he felt as though he had not received enough of an education in surgery, anesthesia, and other cutting-edge medical advancements. So he continued his education at Jefferson Medical College for additional, more specialized training. This was unheard of at the time, as the most common way to become a doctor, even for a person of means, was apprenticeship. He later returned to Lynchburg to open his own practice in 1853 as one of few doctors with a formal education.

Prior to the Civil War, he was, like most doctors of the age; a jack-of-all-trades in the medical field. He travelled on horseback to his patient’s homes and treated injuries and illness, delivered babies, extracted teeth, performed surgeries and provided just about any medical treatment a person may have needed. He prepared his own medicines from medicinal herbs that he grew near his practice, and was particularly interested in disease transmission and treatment. The little white house here at Old City Cemetery, where the Pest House & Medical Museum is now staged, was actually the building where Dr. Terrell ran his medical practice after the Civil War. It was moved to the Cemetery in 1987 from his farm in Campbell County, Rock Castle. The Southern Memorial Association restored the building to recreate and interpret medical science of the era. The medical office and Pest House exhibits have been joined in this museum to give a more complete picture of nineteenth-century medicine, while still telling two very separate stories.

Though he wanted to abandon his practice and join the Confederacy after the Civil War broke out, Dr. Terrell was too valued as a physician and was asked to remain a civilian and continue his practice. However, as the war intensified in 1862, President Jefferson Davis issued a draft (the first ever in American history). Wealthy men were offered the option to hire a slave or someone of lower class to go to war in their place, and Dr. Terrell found this to be morally reprehensible. So he refused to do so, even as Surgeon-in-Chief of Lynchburg, and the Secretary of War for the Confederacy urged him to. Eventually, he mustered into service as Captain John Jay Terrell, Assistant Surgeon in the Confederate Medical Department. He was stationed at the Burton Factory Hospital – one of 19 Lynchburg tobacco warehouses to be converted to Civil War hospitals.

continue his practice. However, as the war intensified in 1862, President Jefferson Davis issued a draft (the first ever in American history). Wealthy men were offered the option to hire a slave or someone of lower class to go to war in their place, and Dr. Terrell found this to be morally reprehensible. So he refused to do so, even as Surgeon-in-Chief of Lynchburg, and the Secretary of War for the Confederacy urged him to. Eventually, he mustered into service as Captain John Jay Terrell, Assistant Surgeon in the Confederate Medical Department. He was stationed at the Burton Factory Hospital – one of 19 Lynchburg tobacco warehouses to be converted to Civil War hospitals.

During the Civil War, infectious disease caused far more death than bullets and bayonets. In fact, about two thirds of CW deaths were from disease. With the lack of immunity to certain diseases (not fully understood at the time) and the cramped conditions of the Lynchburg’s hospitals and the city itself, which had more than doubled in population since the beginning of the war, horrible diseases such as smallpox caused perhaps more fear in Lynchburg than the threat of an advancing Union army. The House of Pestilence, or “Pest House,” was used as a quarantine and treatment hospital throughout the 1840s and 50s for people with contagious diseases like smallpox, cholera and scarlet fever. But as war raged on, it became overrun with infected soldiers.

No one wanted to work in the Pest House. The conditions were unspeakably horrible. Death was a constant. The stench was indescribable. Nurses and care takers drank liquor on the job to deal with the squalid environment, and the psychological toll it took on them. In the midst of war, the doctor who managed it had abandoned it all together. Dr. Terrell, knowing of the desperate need for better care for patients at the Pest House, and knowing that no doctor wanted to take up the job, volunteered to take it over, stating that his “work was to relieve the suffering of humanity, and he would go where he could do the most good.”

The Pest House was located at the outermost edge of town, on land next to the Public Burying Ground (or City Cemetery). Though the original structure is lost to time, it actually stood behind the Cemetery Center, just a few yards down the hill and across the railroad tracks on what is now Black Water Creek Trail. The medical care and standards of cleanliness we know today were virtually non-existent, and most patients died. The dead were buried only a few yards away, here on our grounds.

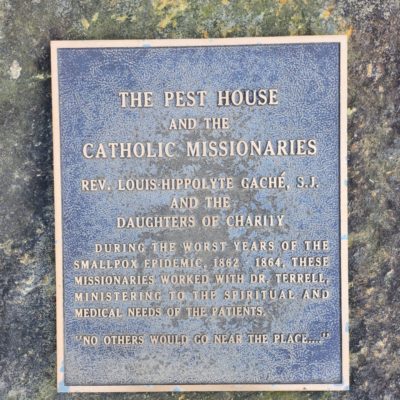

When he began his work at the Pest House, Dr. Terrell was given a blank check for anything he needed to improve the conditions. He asked for 3 things: to report directly to Dr. Owen, the Chief Surgeon, with no middle man, to hand-pick 3 nurses to work with him, and to have all the vegetables, milk and whiskey he wanted. He travelled with a priest, Rev. Gache, and a few courageous nuns who tended to the spiritual needs of the infirm while Dr. Terrell tended to the physical. He had the nuns, the priest and all of his nurses (very few) inoculated with cowpox, which he maintained as a live virus and collected from enslaved children. Though there was no vaccine for smallpox (or for anything), the inoculation did protect his staff from becoming infected. He immediately went to work on improving the sanitation practices and treatment of patients in the Pest House. Many of his colleagues teased him for his attention to sanitation. He was mocked for washing his instruments and requiring his assistants to be sober – two things we wouldn’t even consider flexible today. He remained in the Pest House through Lynchburg’s small pox epidemic, as the Civil War raged on and soldier after solder was delivered to his door to be treated for infectious disease.

When he began his work at the Pest House, Dr. Terrell was given a blank check for anything he needed to improve the conditions. He asked for 3 things: to report directly to Dr. Owen, the Chief Surgeon, with no middle man, to hand-pick 3 nurses to work with him, and to have all the vegetables, milk and whiskey he wanted. He travelled with a priest, Rev. Gache, and a few courageous nuns who tended to the spiritual needs of the infirm while Dr. Terrell tended to the physical. He had the nuns, the priest and all of his nurses (very few) inoculated with cowpox, which he maintained as a live virus and collected from enslaved children. Though there was no vaccine for smallpox (or for anything), the inoculation did protect his staff from becoming infected. He immediately went to work on improving the sanitation practices and treatment of patients in the Pest House. Many of his colleagues teased him for his attention to sanitation. He was mocked for washing his instruments and requiring his assistants to be sober – two things we wouldn’t even consider flexible today. He remained in the Pest House through Lynchburg’s small pox epidemic, as the Civil War raged on and soldier after solder was delivered to his door to be treated for infectious disease.

One of the changes in practice in the Pest House made by Dr. Terrell was painting the interior walls black to reduce strain on the patients’ eyes and cause them to rest better. Another was to spread sand on the floor to dampen the sound in the hospital and to absorb bodily fluids. He also sprinkled lime into the sand to reduce the horrible stench of the Pest House. While these practices all made the patients more comfortable and rest better, they were not Dr. Terrell’s most important breakthrough.

For most soldiers in the field as well as the hospital, the common meal was cornmeal of some kind and, when it was available, a bit of meat (often pork). Dr. Terrell, however, believed that the convalescing soldiers needed more in their diet. He knew that sauerkraut helped reduce scurvy which his patients did not suffer from; however, he believed that the fermented cabbage could still benefit those under his care. Although Dr. Terrell did not fully understand the benefits of sauerkraut, it provided the sick soldiers with important fiber, vitamins, and probiotics which greatly improved their condition. When Dr. Terrell took over the Pest House, the death rate was 50%. After he introduced these new practices, the death rate dropped to just 5%

Click HERE to see the Digital Civil War Brochure, including a map of the Civil War section.

Dr. Terrell changed the landscape of medicine in Lynchburg and the surrounding area. Not only was he willing to use new and advanced medical technology of the time, he also developed tools and medicines specifically to treat certain illnesses. He was the first known physician to to make changes to the environment of smallpox patients to help ease suffering. He was also the first to recognize their need for a specific diet. Below are only a few of his contributions to medicine in Virginia and beyond:

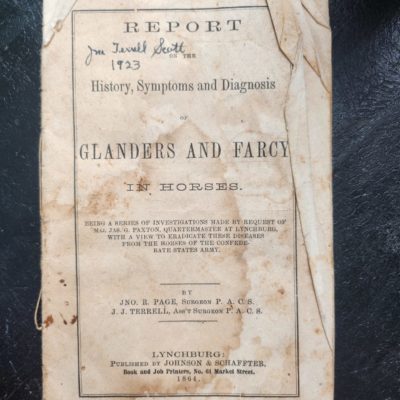

During the Civil War, an epizootic known as Glanders was infecting cavalry horses, which were vital to operations on both the Union and Confederate sides of the conflict. The respiratory illness was fatal, and horses were dropping at an alarming rate. Dr. Terrell, along with Dr. John R. Page, were tasked by the head Quartermaster to research the illness and look for cures. The research was conducted in a special stable where the sick animals were quarantined, either on or very near to what is now the Old City Cemetery grounds. After conducting what became known as a landmark study, including examining the virus in both living and deceased animals, they determined that the illness was caused by the sharing of water troughs, nuzzling between horses, and the cramped conditions of the stables. The quartermasters were then able to take measures to reduce the spread of the disease, and save an unknown number of horses and mules.

To read our brochure on Glanders, click HERE.