Grave Coordinates: Unknown; Likely Reburied at White Rock Cemetery

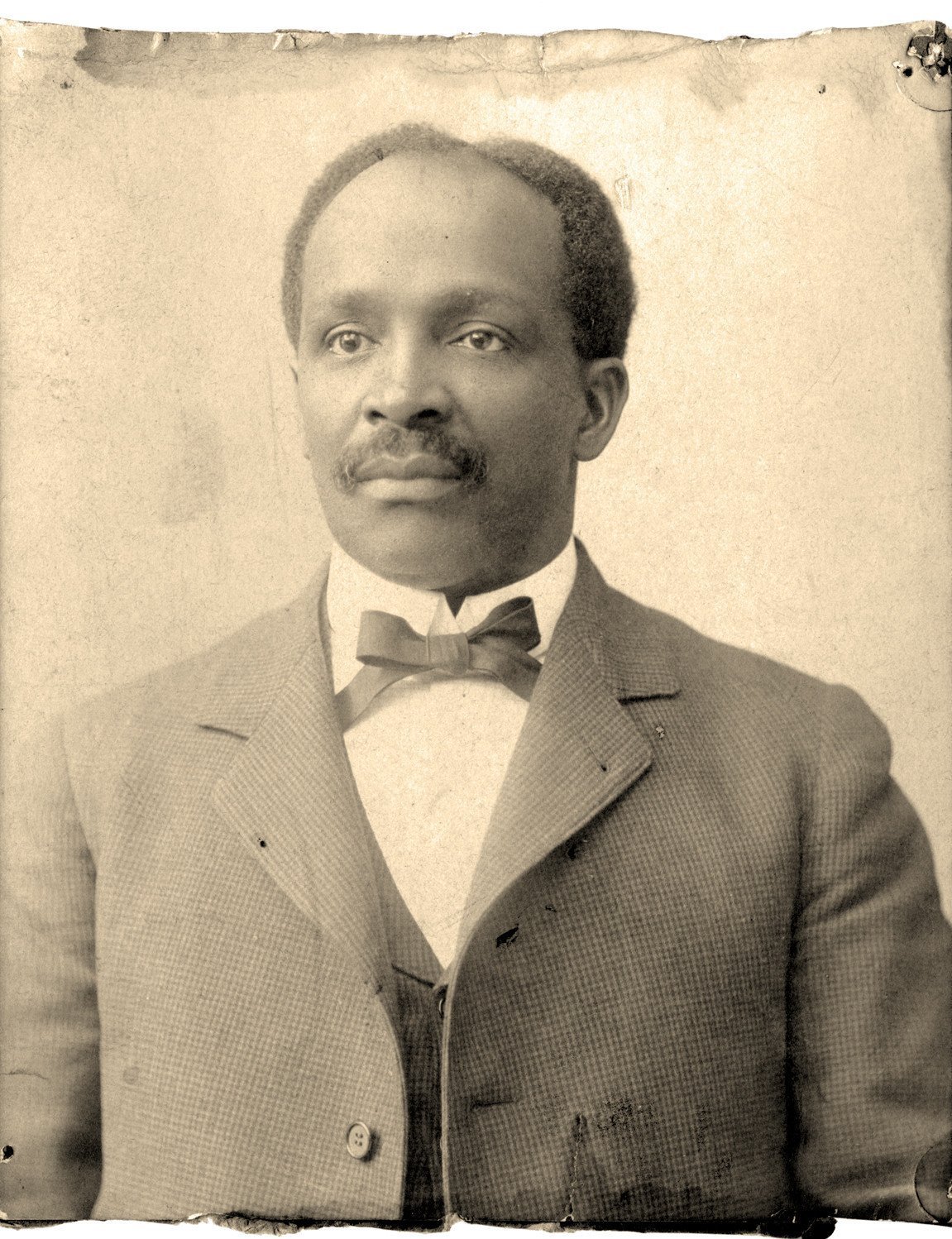

Mybe Otabenga (known today as simply “Ota Benga”), a native of the Congo in central Africa, was exhibited at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair as an exotic “pygmy.”

While many of the details of his early life and his travel to the United States are lost to history, we know that Mybe Otabenga was brought to this country by Samuel Phillips Verner, a businessman and Presbyterian missionary to the Congo. Verner had made arrangements with the Smithsonian Institution to bring a group of “pygmies” from the Congo for an anthropology exhibit at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Verner later gave varying accounts of how he first encountered Ota Benga, but common to most of them was that Ota Benga had been married and had a child, that he had been forced into slavery, either by a neighboring tribe or by forces of the Belgian-controlled government, and that Verner had saved him from either slavery or death at the hands of cannibalistic enemies.

Ota Benga, along with four other men from another tribe, accompanied Verner to St. Louis. The group was displayed, along with ethnic groups from other parts of the world, at the Exposition. At the end of the exposition, Verner returned the Africans to their homeland. Verner had acquired a license from the Belgian government to trade in ivory and rubber, and traveled extensively in Central Africa, possibly accompanied by Ota Benga. For reasons not recorded, Benga chose to return to the U.S. with Verner in 1906.

Verner arranged for accommodations for Benga at the American Museum of Natural History, but in September 1906 he had moved him to the New York Zoological Gardens (known informally as the Bronx Zoo), where the director, William Temple Hornaday, displayed him in a cage with an orangutan. This outraged the Rev. R. S. MacArthur, who organized other Black ministers to protest Benga’s inhumane treatment. Because of growing public outrage, Benga was moved within weeks to an orphanage, the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. At about 20, Benga was older than the other 265 residents and was afforded his own room. Prof. Gregory W. Hayes, president of Virginia Theological Seminary and College in Lynchburg (now Virginia University of Lynchburg), who had participated in the protest against Benga’s display at the zoo, took Benga to Lynchburg in late 1906.

Within weeks of their arrival in Lynchburg, Hayes died of renal failure. His widow, the mother of five children, was appointed interim president of the college, and Benga was returned to the orphanage in New York. The orphanage had recently acquired a farm on Long Island and about 30 adolescent boys and Benga were moved to the farm. Three years later, in January 1910, Benga returned to Lynchburg and the Hayes home. Attempts were made to assimilate him into Lynchburg life. Either in New York or Lynchburg, his teeth, which had been chipped to points in childhood, were capped. He was tutored by Anne Spencer, who taught at Virginia Theological Seminary and College and would later become a celebrated Harlem Renaissance poet, and played with Anne’s son, Chauncey, who would later distinguish himself as a Tuskegee Airman.

Ota Benga, given the name “Otto Bingo” by his hosts, found some comfort in hunting and fishing, often accompanied by neighborhood children, but he longed to return to Africa. Any hopes that he might do so were stymied by World War I. He grew increasingly despondent and eventually took his own life with a gun on March 20, 1916. Chauncey Spencer recalled many years later, “We were told that he thought his soul would go back to Africa.”

Mybe Otabenga—Ota Benga—was buried in a rosewood casket in the Old City Cemetery. The location of the grave and any possible marker have been lost to time. Local oral tradition insists that Benga’s remains were later exhumed and reinterred at White Rock Cemetery although no records of this exist. However, for at least a time, perhaps Ota Benga found rest here at Old City Cemetery.